Minimum Cash Surrender Values and Lapse Immunization

By Matthew R. Farmer

Product Matters!, November 2024

Background

Whole life insurance is a savings product in addition to being an insurance product. Premiums are level while mortality increases with age. The excess premium funds the reserves and reserves build to pay out future death benefits. By paying level premiums, policyholders (on average), defer income in the present to cover higher mortality costs in future. This is an implicit saving activity. Life insurance’s explicit savings component is the cash surrender value (CSV). CSVs are paid to policyholders upon lapse (less applicable surrender charges). Today minimum cash surrender values are governed by standard nonforfeiture law.

However, CSVs were not always offered in life insurance. Elizur Wright, famous actuary from the 19th century, was influential in bringing minimum cash surrender value laws to the United States.[1] Wright held it was unfair for policyholders to receive nothing from the insurance company upon lapse as Wright too believed whole life insurance was a partial savings product.[2] While I acknowledge his point on actuarial fairness,[3] this article approaches the problem from a different standpoint. Namely, the risk reductive benefits of CSVs. By offering CSVs, premiums must increase which is risk reductive. On the liability side, surrender benefits and death benefits offset one another. If lapses are higher than expected, then projected death benefits decrease, and surrender payments increase. I refer to this dynamic as lapse immunization, where insurance products become more lapse-neutral[4] by offering a CSV. To highlight lapse immunization, I present a case study comparing life insurance products with and without CSVs. I must acknowledge that traditional whole life is not without limitations. The product’s viability broke down in the 1970s and 1980s with rising rates and high inflation.[5] I conclude this article by analyzing these limitations. This article focuses on stock insurance companies as opposed to mutual insurance companies.

Lapse Immunization Case Study

In this article, I argue that the imposition of cash surrender value reduces a company’s sensitivity to lapse rates. I also contend that lapses are more difficult to predict than mortality. As an empirical example, there exists far fewer industry lapse tables than industry mortality tables. I further contend lapse risk can be material. As an example, long-term care insurance (LTCI) suffered from an overestimation of lapse rates and has no CSV. LTCI is extremely[[6]] lapse supported. Carriers originally estimated around 5% ultimate lapse rates but, these rates materialized to be around 1% or lower[[7]] which increased benefits paid.

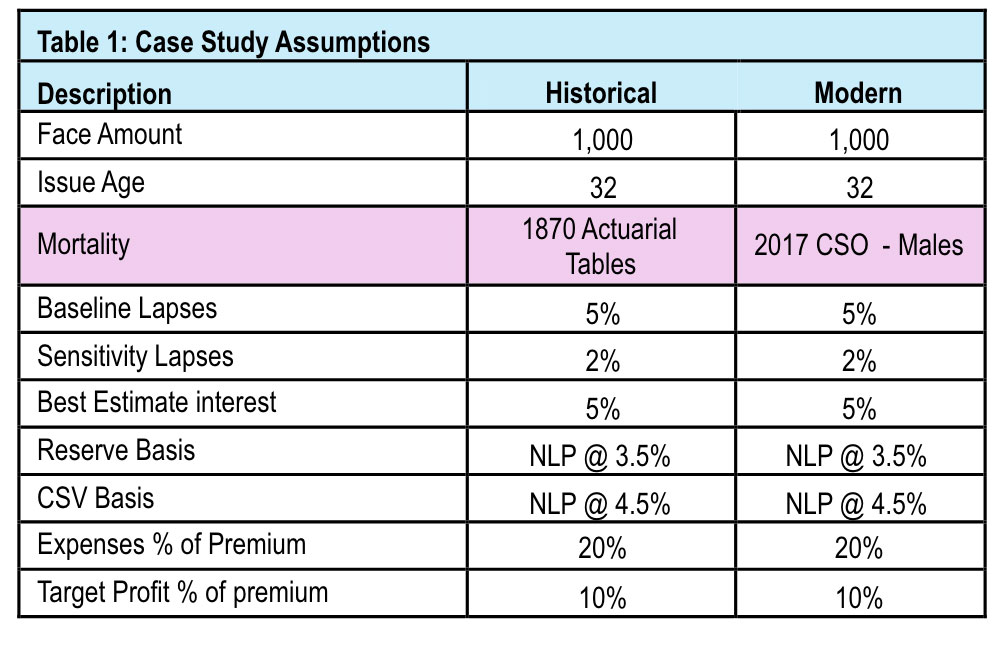

Now let’s introduce the case study. Table 1 summarizes the assumptions used. I have developed two scenarios, the first using mortality tables from Wright’s book (Historical) and the second with the 2017 CSO table (Modern). Comparing the two scenarios illustrates how mortality levels influence the savings component. Present value of pre-tax income was the main metric used. I calculated premiums and projected pre-tax income using simplifying assumptions. Within each scenario I calculated a 2% (from 5%) lapse sensitivity to estimate the impact to pre-tax income. The goal of this case study is to show that cash surrender values offset death benefits and partially immunize the insurer to lapses.

Table 1

Case Study Assumptions

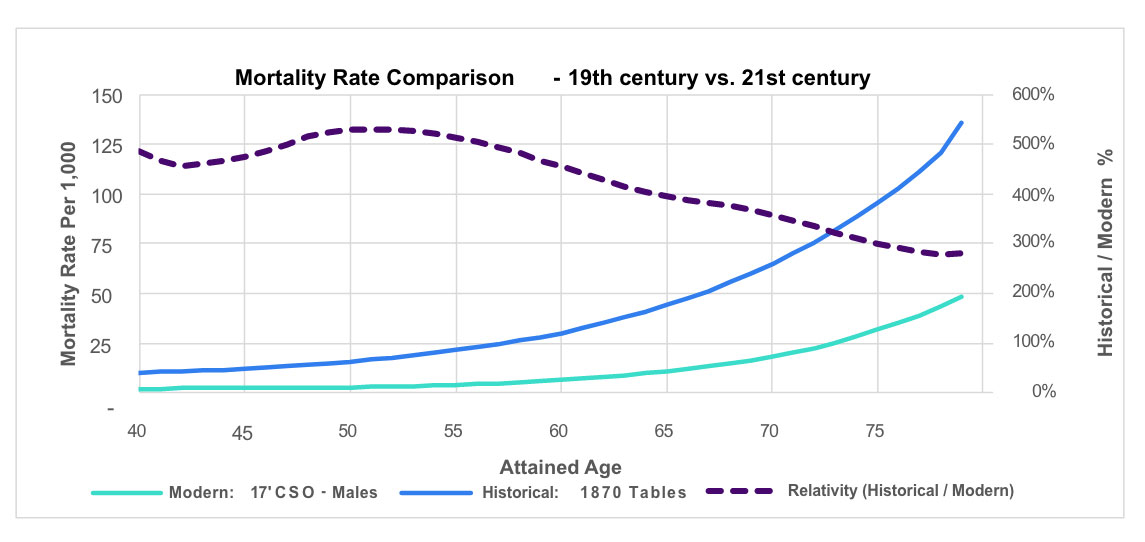

Figure 1 summarizes the mortality tables used. Unsurprisingly, mortality improved significantly since the 19th century. This relates to the case study because fewer deaths mean premium dollars (relative) must be distributed elsewhere. A greater proportion of premium dollars must now be distributed to surrender benefits.

Figure 1

Mortality Rate Comparison – 19th Century vs. 21st Century

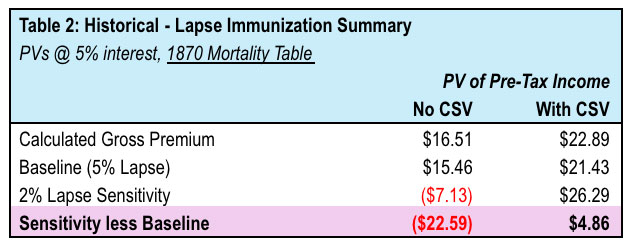

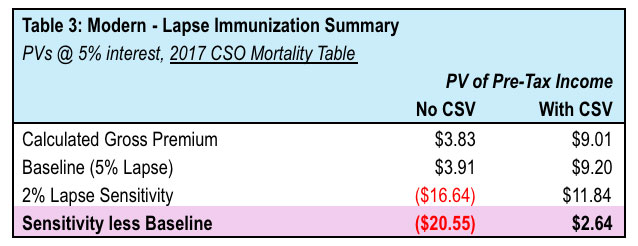

Tables 2 and 3 present the results. Under both scenarios, the product became less sensitive to lapses when a CSV is offered. Further, by having a CSV, premium increases and so do profits (in dollars) allowing a company to grow their premium base.

Table 2

Historical – Lapse Immunization Summary

Table 3

Modern – Lapse Immunization Summary

From these results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

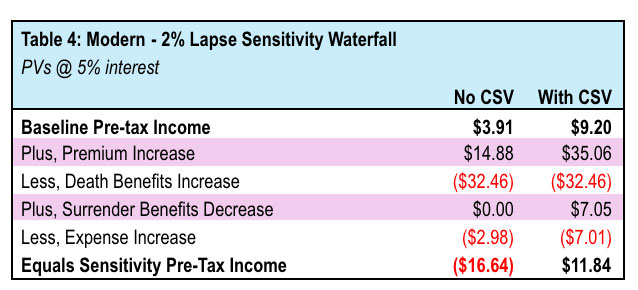

- CSV offsets death benefits. The driver is the increase in premium which allows the company to better handle low lapse scenarios. See table 4.

- Lower mortality rates in the modern scenario made the no CSV product relatively more sensitive to lapses given deaths occur later.

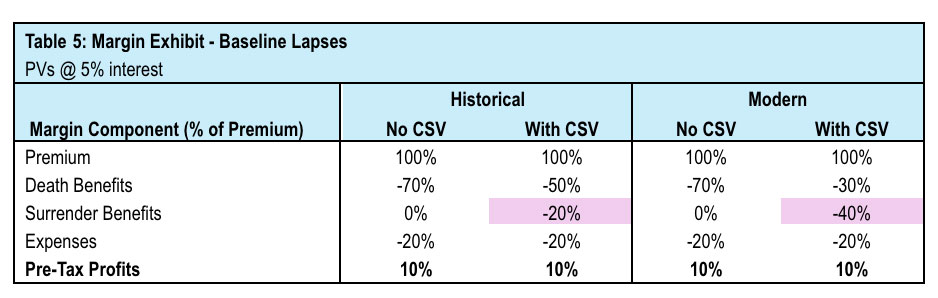

- Significant mortality improvement has made life insurance products more savings oriented. In my illustrative example, the amount of premium dollars distributed to surrender benefits increased by 20 percentage points, when moving from Historical to Modern. See table 5.

Table 4

Modern - 2% Lapse Sensitivity Waterfall

Table 5

Margin Exhibit - Baseline Lapses

This illustrative case study does have limitations. I have simplified expenses, profits, reserve calculations, and CSV calculations. Further, lapse timing matters as early lapses cause the insurer to not recoup the policy’s up-front acquisition expenses. Lastly, I ignored disintermediation risk (see next section). This example is intended to show comparative liability impacts.

Limitations of Traditional Whole Life and Minimum Cash Surrender Values

While minimum cash surrender values provide lapse immunization benefits, there are limitations with traditional whole life’s product design. This product’s fixed premiums and fixed crediting rate (nonforfeiture interest rate) make it slow to adapt to changes. I will now cite another famous actuary, Jim Anderson. Anderson was critical of traditional products and influential in increasing universal life’s prominence in the United States. Three of his criticisms are below:

- Disintermediation risk

- Inadequate savings

- Consumer changes

Anderson’s three criticisms highlight that whole life insurance was too inflexible to be viable in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, interest rates were rising and therefore Anderson feared the disintermediation risk.[[8]] When interest rates rise, policyholders may seek out alternative products with better savings benefits. To pay surrender benefits, the insurer may need to sell fixed income assets at lower market values. Further, fixed crediting rates in a rising rate environment made inflation more costly to policyholders and they were not achieving adequate savings rates. Alternatively, universal life has flexible crediting rates which is generally risk reductive to the insurer and can offer policyholders more competitive savings rates. Further, Anderson argued that universal life’s flexible premium better accommodated changing consumer attitudes at that time.[[9]] Lapse immunization is still applicable to universal life as the fund value (less surrender charges) is paid to policyholders upon lapse. The key differentiator is the flexibility. This allows universal life carriers to better respond to the external environment and balance competitiveness with risk.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Society of Actuaries, his employer nor the actuarial profession.

Matthew R. Farmer, FSA, is a Senior Actuarial Consultant at WTW. He can be reached at Matthew.Farmer@WTW.com.

Endnotes

[1] American Academy of Actuaries, Report of the Nonforfeiture Improvement Work Group (American Academy of Actuaries, 2011), 37–38.

[2] Elizur Wright, Politics and Mysteries of Life Insurance (Classic Reprint) (Shepard Publishers: 1873; repr., Leopold Classic Library, 2018), 46–47. Citations refer to the Leopold Classic Library version.

[3] Noting premiums increase if cash surrender values are offered.

[4] As opposed to lapse-supported or non-lapse-supported.

[5] James C.H. Anderson, The Papers of James C.H. Anderson (Society of Actuaries, 1997), 261, 279–280 & 306.

[6] Especially when combined with rich benefits (e.g., inflation protection) and decreasing interest rates in the 2000s.

[7] Robert Eaton and Matt Morton, Insuring Long-Term Care (Actex, 2022).

[8] See Supra note 5.

[9] Anderson, The Papers of James C.H. Anderson, p. 62–64.